|

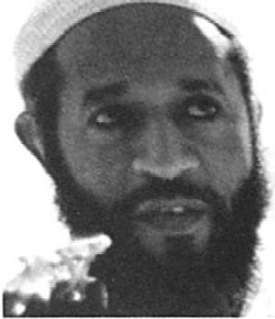

Dr. Rashidaka Clement Rodney Hampton-El

Clement Rodney Hampton-El, better known as Dr. Rashid, was a strange cross between Batman, Mother Teresa and Ramzi Yousef. Terrorists are generally a weird bunch, but Rashid ranks up there as one of the weirdest. His story is almost whimsical, or it would be, if not for the fact it ends with a failed plot to blow up New York City tunnels and landmarks with truck bombs. Born in 1938, young Clement was raised by his parents as a God-fearing member of the Moorish Science church, a weird forerunner of the Nation of Islam. As a member of the Moorish Temple, he wore a fez and proclaimed his belief in black empowerment via flaky New Age beliefs purportedly somehow connected to Islam. Hampton-El joined the Army in 1957, but it didn't suit him very well. He found racism to be rampant among his fellow soldiers. Flaky beliefs or not, Moorish Science adherents were not known to accept racial harassment meekly. Things boiled over. "Finally, some guys came into the barracks and they said, 'You know, you're a dead nigger.' I thought they was just saying a lot of crap, you know." They weren't. Hampton-El was jumped by his fellow soldiers. He fought back but got knocked out. When he woke up, he was in the stockade. Since he was black and his assailants were white, Hampton-El ended up getting a dishonorable discharge (which he later successfully appealed).

On leaving the Army, he went to work as an EMT, eventually taking a job at the Long Island Hospital in New Jersey, where he would work for nearly 30 years. He worked in the hospice wing, where he provided care to terminally ill patients. His fellow employees saw him as an unusually gentle and caring man, who was willing to do dirty jobs like cleaning up patients who had shat themselves. In 1967, Hampton-El was walking near his home in Brooklyn, when he noticed a group of Muslims standing outside a mosque on State Street, laughing at his fez. He asked them what they were laughing at, and they told him "What you are practicing is not really true Islam." Clement came back the next day and began studying Islam at the mosque. He adopted the Islamic name Abdul Rashid Abdullah, but he went by Rashid. Rashid was considered a community leader. He was widely respected by his neighbors and well-regarded at the mosques where he worshiped. He was deeply involved in community affairs, at the mosque and his apartment project, where he helped organize efforts to drive out drug dealers. Unlike your typical "crime watch," however, Rashid was active in his efforts. A student of martial arts, Rashid patrolled the streets dressed in a ninja costume, supposedly chasing down crack dealers and protecting the innocent. But it wasn't all super-heroics and caring for the terminally ill. Rashid had a lot of other stuff going on too. In 1988, for instance, he took a trip to Pakistan and Afghanistan, to volunteer his services as a mujahideen in the jihad against the Soviet Union. He made his arrangements through the Alkifah Refugee Center in Brooklyn. Officially, Alkifah was a branch of the Services Office, a Pakistan-based operation designed to raise funds and volunteers for the U.S. funded jihad. Because the war in Afghanistan was a CIA pet project, Alkifah didn't get a lot of scrutiny from law enforcement or intelligence services, even when it sponsored seminars featuring self-professed terrorists as keynote speakers. The Brooklyn office arranged for Rashid to meet up with the mujahideen on his arrival in Pakistan. When he arrived, the jihadists he met wanted to sign him up for religious indoctrination and combat training, but Rashid explained he only had a month off from his job, so he needed to wade right on out into the holy war. Fortunately, he explained, he had already been trained in combat by the U.S. Army, so he didn't need to train.

Later, prosecutors would argue that Rashid received actually did attend training in Afghanistan, specifically on the topic of bomb-making (Rashid denied this and said he spent his first few weeks in Pakistan bedridden with a case of malaria). Either way, most accounts agree that Rashid served the jihad as a battlefield medic (who only incidentally carried a rocket launcher, he explained later). His compatriots called him "Dr. Rashid," a nickname that stuck when he returned to the States. After about a week of action, Rashid stepped on a landmine and blew half his leg off. He raided his medical pack to stop the bleeding, then waited nearly 18 hours before he was evacuated from the battle scene to a Saudi-funded hospital in Peshawar. He returned to the United States for more hospital care. Despite his short tenure in Afghanistan, Rashid had apparently become a major mujahideen celebrity. (The only account of his time in Afghanistan comes from Rashid himself, so it's quite possible there were other reasons for his celebrity status that have not been revealed to the public.) After he emerged from the hospital, Dr. Rashid was a much sought-after motivational speaker. His talks dealt with devotion to Islam, liberally sprinkled with exhortations to join the jihad. Rashid traveled around the country, attending Islamic seminars and giving speeches at local mosques. His home base continued to be Brooklyn, the Alkifah Center and a nearby mosque, Al-Farooq. As the 1980s gave way to the 1990s, big changes were taking place within Dr. Rashid's Brooklyn Muslim community.

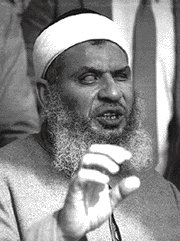

In 1990, Sheikh Omar Abdel Rahman arrived in New York. Known as the "blind sheikh," the visually impaired Rahman was a fiery fundamentalist preacher with ties to three major Egyptian militant groups - Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, the Muslim Brotherhood and Egyptian Islamic Jihad, a terrorist network controlled by Ayman Al-Zawahiri. Rahman was a notorious firebrand, who was tried and acquitted of providing a fatwa authorizing the assassination of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat in 1981. Given his terrorist connections, Rahman's entry into the U.S. was something of a mystery. Rumors swirled that his efforts to obtain a visa were assisted by the CIA. Rahman became the imam of the al-Farooq mosque where Rashid worshiped. An extreme fundamentalist trained in Saudi Arabia and at Egypt's Al-Azhar University, Rahman proved immediately divisive in the community, preaching against Western governments and ostracizing Brooklyn Muslims who sold unclean goods (like pork and porn) to corrupt infidel New Yorkers. Rahman seized control of the Alkifah Center in 1991, when its previous leader was brutally assassinated. Officially, the murder remains unsolved, but it's widely believed that Shalabi was killed on orders from Rahman, who took control of the center's considerable finances and overseas connections. Dr. Rashid was close to Rahman, and they traveled together to speak at Islamic conferences in such locations as Detroit, Chicago and Oklahoma City.

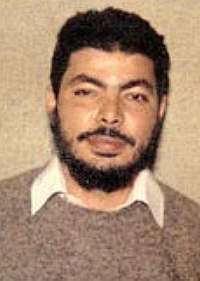

When he wasn't busy preaching, Rashid was preparing for the future. Starting in 1989, Rashid and other radical Islamist began a rigorous program of jihad training, purportedly for volunteers in Afghanistan and Bosnia (where a new jihad was in its early stages). Rashid and other Brooklyn Muslims trained in firearms use at a rifle range in New Jersey, and in guerrilla techniques at a rural camp in central Pennsylvania. The FBI monitored this activity but did nothing about it. It's likely that some of the trainees were already formally part of a terrorist sleeper cell by the time Rahman arrived on the scene, but the "blind Sheikh" galvanized their activities into formal operations. One of the men who trained with Rashid was El Sayyid Nosair, a volunteer at the Alkifah center. Nosair had emigrated to the U.S. from Egypt in the mid-1980s, along with several other terrorist sleeper agents linked to Zawahiri. The first operation carried out by the cell was the assassination of right-wing rabbi Meir Kahane by Nosair. Kahane was an outspoken advocate of deporting all Palestinians out of Israel and he called for the institution of a Jewish theocracy. Nosair shot Kahane in the head during a speech in front of a packed audience of hundreds of people, then shot his way down the street during an escape attempt. Unbelievably, despite an excessive amount of shooting and a room full of witnesses, Nosair was acquitted of the murder and received a relatively short sentence for a federal firearms violation. It later emerged that Dr. Rashid was originally supposed to be Nosair's getaway driver, but he refused to appear on the scene, citing the fact that the FBI had him under close surveillance. Later, Rashid reportedly berated himself for not taking the job, considering that Nosair nearly escaped even without assistance. A driver would likely have made the difference. Although Nosair had been caught, it had little impact on the Brooklyn cell's operations. The FBI had seized cartons of documents from his apartment, but never bothered to translate them from the original Arabic. Had they done so, they would have found clues to proposed terror plots all around the city. They would also have found a document referring to a previously unknown terror organization called "The Base," or in Arabic, al Qaeda.

As the Afghanistan jihad wound down at the end of the 1980s, Alkifah had begun to do more and more business on behalf of al Qaeda, and its wealthy Saudi leader, Osama bin Laden. By the time Dr. Rashid made arrangements to go to Pakistan, al Qaeda was well on its way to becoming the dominant force at the center. Several of the Alkifah Center's "volunteers" were tied to bin Laden and al Qaeda (including Wadih El-Hage, bin Laden's personal secretary, and Ali Mohammed, bin Laden's chief of security), but the U.S. government didn't even know the terror network's name. If they had bothered to translate Nosair's material, and follow up on the leads contained within, they might have been prepared for Ramzi Yousef's arrival in Brooklyn in late 1992. Yousef had been summoned to New York from Pakistan by the blind sheikh. Yousef's work in New York was paid for in part by his uncle, Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, and in part by bin Laden. On his arrival in the States, Yousef joined forces with a cabal of Alkifah-linked terorrists, including Mahmud Abouhalima, another associate of Dr. Rashid's. Dr. Rashid himself was only tangentially connected to Yousef's reason for being in New York, a plot to bomb the World Trade Center. But Rashid was not idle during this time.

After coming back from Afghanistan, Dr. Rashid's career had proceeded on two fronts, neither of which had anything to do with medicine. First, he had established himself as a go-to guy for guns and other jihad supplies, such as explosives and detonators. He paid for weapons from gun shows, local stores and freelance sellers. In addition to his clients providing "security" services at Brooklyn mosques and Alkifah, Rashid made deals with al-Faruq, a clannish group of black separatist Muslims with heavily armed rural compounds around the country. Rashid's other business was international. Toward the end of 1992, while Yousef was busy building a truck bomb that would kill six and injure a thousand at the WTC, Dr. Rashid was doing business on behalf of the Saudis. In December 1992, Rashid went to the Saudi Embassy in Washington, D.C., where he met with high ranking Saudi government officials.

The Saudis had several tasks for the Afghan veteran. Rashid met with a U.S. Marine sergeant who gave him a list of servicemen who were about to rotate out of active duty. Rashid was ordered to recruit terrorists and trainers from the list, some of whom were slated to fight in Bosnia, where al Qaeda was trying to jumpstart a revolution. At one point, Rashid claimed he had thousands of names in his recruitment list, many of which appear to have been collected by the Saudi government during the Gulf War. The Saudis had other jobs for Rashid as well. Early in 1993, while Yousef was blowing up the World Trade Center, Rashid was traveling to Europe where he would ferry large amounts of cash back to the U.S. from wealthy Saudi donors who were trying to protect their identities. Some of the money went to fund terrorist training and operations on U.S. soil, some of it was earmarked for Bosnia. In May, Rashid traveled to Saudi Arabia in person, then to the Philippines, where he attended a symposium sponsored by the Islamic Da'wa Council of the Philippines, a charitable organization that Philippines authorities say was linked to bin Laden's brother-in-law, Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, a Saudi businessman who is alleged to have acted as a top al Qaeda financier. While in the Philippines, Rashid learned about terrorist training camps in the south of the country. When he came back to the U.S., he told his friends that he was planning to move to the Philippines and take part in jihad there. Some of them asked to join him. Before they left, however, there was one more job to do in the United States. In the wake of the World Trade Center bombing in February 1993, several members of the Brooklyn sleeper cell had been arrested or forced to flee the country. The remaining terrorists were determined to follow up on Yousef's opening salvo.

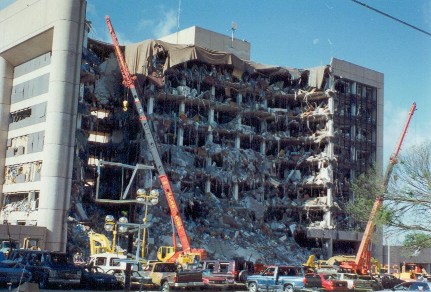

The plot was ambitious. The cell wanted to create a "Day of Terror," with a series of near-simultaneous bombings across New York City. At various stages, the plot looked at tunnels, federal buildings, courthouses and the United Nations as targets. The final list was narrowed down to five, including the U.N., the Holland Tunnel, the Lincoln Tunnel, the George Washington Bridge and the Manhattan Federal Building, which housed the FBI's New York offices. It would be a highly synchronized attack, a style now considered an al Qaeda trademark. The remaining cell members included Siddig Ali, Ibrahim El-Gabrowny, Tarig Elhassen, Mohammed Saleh, and dozens of others associated with the Brooklyn mosque. Only a dozen men were prosecuted for the plot, but a list of unindicted co-conspirators included 172 more names, including Osama bin Laden, Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, and the diplomatic attache from the Sudan (where bin Laden lived). Dr. Rashid's job was to obtain supplies for the plot, including weapons, explosives and detonators. Although hundreds of pages of testimony cited dozens of discussions by the conspirators regarding Rashid's quest to find detonators and other materials for the bomb, it was never clear what material he actually provided to the plotters, if any. Rashid was also believed to have provided some expertise in bomb-building, but the plotters were also supplied with a variety of instruction manuals on the subject, some of which had been purchased at U.S. gun shows. Several members of the cell assembled in a storage locker in New Jersey to start building the bombs, which used components such as homemade nitroglycerin, ammonium nitrate and fuel oil. The bombs would be delivered in stolen cars and trucks. Several of the New York operatives rented a storage space in Queens to prepare their bomb. But for all their preparation, they had failed to obtain one crucial piece of information -– the fact that one of their co-conspirators was actually an FBI informant. The storage space had been wired for sound and video, and the informant had been secretly taping the plotters for months. At 2 a.m. on June 24, 1993, five of the plotters were arrested as they mixed fertilizer and fuel oil for their bombs. Dr. Rashid was not on the scene, but he was arrested early the next morning, outside his apartment.

As a problem in prosecution, the plot was a slam dunk. Thanks to the informant, the FBI had hours and hours of tape, phone taps and physical evidence. During the 1995 trial, in which all the defendents were prosecuted together, Rashid's attorney repeatedly characterized the evidence against his client as "bullshit." The hours of incriminating conversation featuring his client were just "bullshit sessions." (The word "shit" was used in some variation more than 40 times during the trial.) The trial was not without its complications. On April 19, 1995, Gulf War veteran Timothy McVeigh blew up the Alfred E. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The truck bomb was very similar to the ones planned for the Landmarks plot, the target was very similar, the New York suspects had traveled to Oklahoma City and to Michigan, where McVeigh and co-conspirator Terry Nichols had lived, and Dr. Rashid had traveled to the Philippines, where Nichols and Ramzi Yousef had both spent several months in 1994. Both Nichols and McVeigh had sold weapons at gun shows across the U.S., and the New York suspects had bought weapons at similar shows. Faced with all this, the court had to make a decision –- complicate an already complicated case by declaring a mistrial and waiting for possible new evidence, which might not ever surface, or continue as if nothing had happened. After several days of lesser instructions, the judge announced to the jury on April 24: "I think we already know enough about that matter to be able to say that that bombing not only had absolutely nothing to do legally with this case, but also in fact cannot possibly be connected in any way with any defendant in this case." It was an extraordinary statement, considering that FBI agents were at that moment traipsing around the Philippines interrogating Nichols' associates about his possible connections to Islamic extremists. There were other possibilities as well. Although it wasn't widely known at the time, Islamic evangelists working for the Saudi government had collected the names of thousands of U.S. servicemen during the Gulf War, with the goal of converting them to Islam, as reported by the Washington Post. Most of the names were collected in Riyadh, where Timothy McVeigh had briefly been stationed. The Saudi official in charge of the program distributed the names to U.S. operatives who followed up with the soldiers. The official who ran the Riyadh program was the same Saudi cleric who provided Dr. Rashid with a list of former servicemen to recruit as terrorist trainers.

Regardless of these bits of trivia, the trial went on and the U.S. government never produced evidence of a link between the two cases (whether or not such evidence existed). Based on hours of surveillance tapes, copious physical evidence and weeks of testimony by government informants, the jury returned a round of guilty verdicts in October 1995. Dr. Rashid, under his birth name of Clement Rodney Hampton-El, was sentenced to 35 years in prison, better than some of the defendants but worse than others. Today, at age 66, Dr. Rashid has traded his ninja superhero costume for a prison jumpsuit. Rashid's sentence expires in 2023; he could conceivably live long enough to see daylight again. He lives out his days in a tiny, restricted cell in Colorado's Supermax prison, one of the most secure federal facilities in the country, alongside such notorious criminals such as Ramzi Yousef, the Unabomber, Terry Nichols and Woody Harrelson's dad (pictured at right). Which means he's keeping company with a September 11 conspirator, an Oklahoma City conspirator and an alleged Kennedy Assassinations conspirator. Woody Harrelson's dad was one of JFK's assassins? Even in prison, Dr. Rashid keeps some strange company... |