|

John Paul II Like Lesane Parish Crook or Cherilyn Sarkisian LaPierre, Karol Jozef Wojtyla will be remembered by the name he adopted rather than the one he was born with.

Like Lesane Parish Crook or Cherilyn Sarkisian LaPierre, Karol Jozef Wojtyla will be remembered by the name he adopted rather than the one he was born with. Wojtyla was born in 1920 near Krakow, Poland. His father was a retired soldier in the Polish Army (insert your own joke here), and his mother was a teacher in the Polish school system (insert your own joke here). His mother died when Karol was nine years old (no joke here, you heartless bastard). Contrary to what you might have thought to look at him in his final years, young Karol was a robustly athletic young man, who skied, hiked, swam and played soccer. His indefatigable physical prowess slowed a bit when he was hit by a truck in college, leaving him with a slight hunch, but by every account, he was a pretty healthy guy. Indeed, by the look of him, there was nothing that said "future pope." Of course, for the past 400 years, all popes had been Italian, so there wouldn't be. Even putting that factor aside, Wojtyla led a fairly secular life of the day. He went to college, studied theater and singing, then worked as a stone cutter after the Nazis invaded in 1940.

As a priest, his studies were facilitated by his posting as a Krakow university chaplain. Unfortunately, Poland's post-Nazi era saw the rise of Communism, which was even more unfriendly to the Church. Wojtyla climbed the ladder to become archbishop of Krakow, and then rose to the rank of cardinal in 1967. As a Catholic working in an occupied land, Wojtyla generally followed the traditional Catholic practice of appeasement. He fought just enough to keep the Church meaningfully intact, but not enough to significantly piss off the Commies. Wojtyla played an integral role in the reforms of Vatican II, which dispensed with the Latin Mass and encouraged Catholics to get involved with their religion. He also wrote a series of academically well-received books and papers on topics including the relationship between religion and philosophy, and a Catholic concept of sexuality.

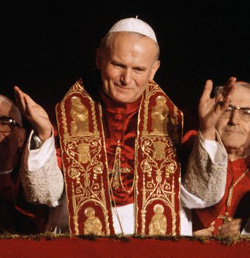

In 1978, in an election shocker, Wojtyla was chosen to succeed Pope John Paul I, who had died under what must be described as reasonably suspicious circumstances after barely a month in office. For a variety of reasons, the cardinals had determined that it would be good politics to take the papacy away from the Italians, and Wojtyla made for a politically interesting selection at the height of the Cold War. Wojtyla took the name John Paul II, perhaps as a message to anyone who might allegedly have done away with John Paul I. He made a triumphant victory tour through Poland, where he was greeted by incongruously adoring Communist crowds, which in turn made the leaders of the Soviet bloc very nervous.

John Paul's iconic status was cemented in 1981, when he was the subject of an assassination attempt. A little more than a week before the attack, a Trappist monk hijacked an airplane full of passengers and demanded that the Vatican release the Third Secret of Fatima, a prophecy supposedly delivered several decades earlier by the Virgin Mary. The relevance of this incident may not be immediately apparent, but stick with us here. On 13 May, 11 days after the hijacking, the pope was shot by a would-be murderer. John Paul was hit, but not killed, by the assassin's bullet. Recovering in the hospital, J.P. was purportedly divinely inspired to realize that the Virgin Mary had saved his life. He immediately summoned the third secret from the Vatican vaults and read it. According to the official church position, which is less than unassailable, the secret foretold the assassination attempt which had now been averted. It's not clear why the Virgin Mary would be wrong, but there it is.

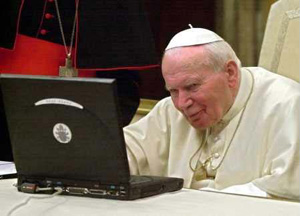

In contrast, there was absolutely no question that the next attempt on the pope's life was the product of a wide conspiracy. Uber-terrorist Ramzi Yousef crafted a plot to assassinate the Pope in 1995 during a trip to the Philippines. This attempt, funded by Osama bin Laden through his brother-in-law Mohammed Jamal Khalifa, never got to the point of a shot being fired, but when local police broke up the al Qaeda cell they discovered that Yousef had stocked up priestly costumes and rented an apartment with a view of the pope's parade route. It was another close call, Virgin Mary notwithstanding. John Paul II was often touted for attempting to restore a church fragmented by battling liberal and conservative branches around the world, trying to update church teachings to deal with the rapidly expanding ethical issues created by technological advances. But his early successes were largely lost in the later years of his papacy.

John Paul made one last bid for relevance as he attempted to dissuade the U.S. from invading Iraq. The effort backfired, as the pope's plea for peace barely edged out headlines about the search for nonexistent weapons of mass destruction.

"It's a mistake to apply American democratic procedures to the faith and truth. You cannot take a vote on the truth," John Paul observed. While he may have had a point as far as the latter statement, the former statement rang hollow at the opening of the 21st century, when the American church plunged deep into crisis over the issue of priests who love boys too much. It wasn't exactly a big shock that Catholic priests were diddling the altar boys. When the first sordid tales began trickling out of the Boston Archdiocese in January 2002, the idea had already been lurking at the edge of the zeitgeist for a long, long time.

But for most Catholics, the over-the-top unacceptable revelation was that the church had actively covered up the pattern of pedophilia among priests working with children. In Boston, the archdiocese had been tracking cases of unsanctified molestation for decades. More stories began to emerge from around the United States. It became painfully clear that Cardinal Bernard Law, the archbishop of Boston, had done more than his fair share of covering up his subordinates' sins of emission.

John Paul accepted the resignation -- but only reluctantly, according to a million anonymous Vatican insiders, who insisted that the pope believed the church could not be held to account for thousands of cases of pedophilia, even if the church itself had authorized hiding the crimes from local law enforcement. A 2002 story in the Boston Globe reported that: "For an institution that measures time in centuries, not network news cycles, Vatican insiders said it was an extraordinarily swift and forceful response and a profound recognition that the Vatican had finally come to understand the depth of the crisis in the American church." But the definition of "swift and forceful" understood by Vatican insiders came into question, as Cardinal Law was transferred to a cushy pre-retirement posting in Rome.

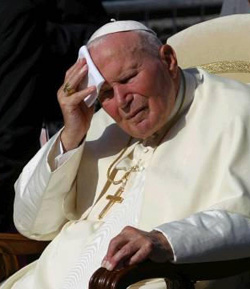

John Paul's response was further muted by the slow but steady deterioration of his health. Since the late 1990s, every public appearance made the pope was inevitably followed by the echoes of a couple billion people simultaneously sighing, "Man, he looks bad."

By the time the priestly pedophila scandal reached its height, the pope's public appearances were increasingly grim and dominated by the frailty of his voice and appearance. The message about the scandal was half-hearted in content and barely a quarter-hearted by the time it had passed through the filter of John Paul's failing body. In early 2005, John Paul II was entered his final days. After another case of "the flu," he began an extended hospital stay on 1 February, while the world watched and wondered. At an unhealthy 85, things were looking pretty grim, sparking a lot of speculation that he might take the unprecedented step of resigning for health reasons.

That end came on April 2, 2005. The pope had spent weeks in and out of the hospital, and he missed most of his traditional Easter observances as his health hit disastrous new lows. Ironically, the Vatican had become embroiled in the right-to-die case of Terry Schiavo, an American vegetative brain-damage patient kept alive by a feeding tube, even as John Paul himself was fitted with a similar tube when he became unable to eat. Unlike Schiavo, John Paul did not linger long after the tube was inserted. The world kept vigil by his hospital bed for the final 72 hours.

The selection of John Paul's successor will determine whether the Church can extricate itself from these troubles. If the Vatican returns to the typical elderly Italian insider cardinal for leadership, its relevance could slip away. A younger pope might make changes, especially if he hails from the West or from Africa, as some have speculated. John Paul II might not get his security deposit back on the Vatican. It's tough to argue that he left the Church in the same condition as when he moved in. But he was the pope, and not many people can say that. Many Catholics felt a powerful attachment to the man himself, if not his management skills or theological positions. Can sainthood be far behind? We think not.

|

In 1941, deep into the German occupation of Poland, Wojtyla's father died. Dad had always wanted Karol to be a priest, and the death of a parent under duress will do things to your mind. Wojtyla took up the quest, although he had to study secretly under the Nazi regime. He became a priest in 1946, continuing his studies and eventually earning two masters' degrees and two doctorates.

In 1941, deep into the German occupation of Poland, Wojtyla's father died. Dad had always wanted Karol to be a priest, and the death of a parent under duress will do things to your mind. Wojtyla took up the quest, although he had to study secretly under the Nazi regime. He became a priest in 1946, continuing his studies and eventually earning two masters' degrees and two doctorates. The latter was seen as a positive thing, in the context of the religious tradition which preceded it, acknowledging a role for sexual urges in healthy lives. His reputation for progressiveness on sexual issues would be short-lived, however.

The latter was seen as a positive thing, in the context of the religious tradition which preceded it, acknowledging a role for sexual urges in healthy lives. His reputation for progressiveness on sexual issues would be short-lived, however.  In addition to his unprecedented Polishness, he was also one of the youngest popes in recent memory, and he soon became wildly popular among Catholics, inasmuch as the phrase "wildly" could be associated with an increasingly tepid Roman Catholic institution.

In addition to his unprecedented Polishness, he was also one of the youngest popes in recent memory, and he soon became wildly popular among Catholics, inasmuch as the phrase "wildly" could be associated with an increasingly tepid Roman Catholic institution.  The shooter was a Turkish Muslim named

The shooter was a Turkish Muslim named  In his role as the architect of Catholic dogma, John Paul II adamantly rejected any movement on several key social issues of the day, rejecting changes in social climate in favor of the church's traditional positions on

In his role as the architect of Catholic dogma, John Paul II adamantly rejected any movement on several key social issues of the day, rejecting changes in social climate in favor of the church's traditional positions on  Most of these positions played particularly badly with an American audience, to which John Paul responded by pointing out that the Church is not a democracy.

Most of these positions played particularly badly with an American audience, to which John Paul responded by pointing out that the Church is not a democracy.  The surprise wasn't even how many priests had diddled how many altar boys, as well as just plain boys, and even a few girls, although the numbers that began to emerge were truly shocking. In the U.S. alone, hundreds of priests had abused thousands of children, and those were just the documented cases.

The surprise wasn't even how many priests had diddled how many altar boys, as well as just plain boys, and even a few girls, although the numbers that began to emerge were truly shocking. In the U.S. alone, hundreds of priests had abused thousands of children, and those were just the documented cases.  After an agonizingly long year under a media microscope, Law did the American, democratic thing and tendered his resignation on 13 December 2002. Rumor had it that his first attempt to resign was flatly rejected by the Vatican.

After an agonizingly long year under a media microscope, Law did the American, democratic thing and tendered his resignation on 13 December 2002. Rumor had it that his first attempt to resign was flatly rejected by the Vatican. As the resignations mounted, one Vatican-appointed replacement bishop himself had to resign after being implicated in yet another sexual scandal. The Vatican also scaled back reforms proposed by a committee of American bishops. Meanwhile, documents uncovered by the press showed that the Vatican's guidance had encouraged the cover-ups in the first place.

As the resignations mounted, one Vatican-appointed replacement bishop himself had to resign after being implicated in yet another sexual scandal. The Vatican also scaled back reforms proposed by a committee of American bishops. Meanwhile, documents uncovered by the press showed that the Vatican's guidance had encouraged the cover-ups in the first place.  But that speculation was driven by the American, democratic-style concept that someone who is physically incapable of performing a job should not be performing the job. John Paul II informed his flock that he didn't and would hang in there until the bitter end.

But that speculation was driven by the American, democratic-style concept that someone who is physically incapable of performing a job should not be performing the job. John Paul II informed his flock that he didn't and would hang in there until the bitter end.  John Paul's legacy is mixed at best. He left behind a church wallowing through profound troubles. Even before the not-yet-counted damage inflicted by the pedophilia scandal, it was estimated that by 2020 about half of all priests would be older than 70. The communities rocked by pedophilia scandals are getting the old one-two, as soaring church settlements with sexual abuse victims leave more and more parishes struggling with bankruptcy. The number of students in Catholic schools, predictably, is plunging. All around the world, for a number of different reasons, the number of Catholic adherents is on the decline relative to the population.

John Paul's legacy is mixed at best. He left behind a church wallowing through profound troubles. Even before the not-yet-counted damage inflicted by the pedophilia scandal, it was estimated that by 2020 about half of all priests would be older than 70. The communities rocked by pedophilia scandals are getting the old one-two, as soaring church settlements with sexual abuse victims leave more and more parishes struggling with bankruptcy. The number of students in Catholic schools, predictably, is plunging. All around the world, for a number of different reasons, the number of Catholic adherents is on the decline relative to the population.