|

Prester John During the 12th Century, Christendom had firmly abandoned the concept of turning the other cheek in favor of supervillain-scale plans for world conquest.

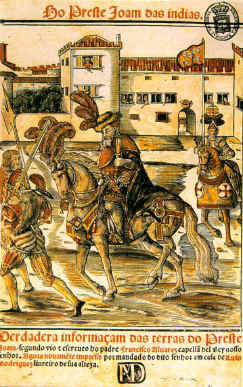

During the 12th Century, Christendom had firmly abandoned the concept of turning the other cheek in favor of supervillain-scale plans for world conquest. Emboldened by the taking of Jerusalem during the first Crusade, the European Christian monarchs of the time were ready to rumble. But seizing the Holy Land and keeping it were two different things, and during a period of open war with Saladin and his Muslim armies, the thought of an unexpected and powerful ally in a strategic location was an alluring prospect indeed. In the midst of all this turmoil, the Catholic leadership received word about a mysterious Eastern priest-king known as Prester John, or Presbyter John, or Priesty Juan, or Priester John, or any one of a dozen or so similar-sounding names. The ambiguity about the name reflected the ambiguity about the person. There are somewhere between dozens and hundreds of versions of the story of Prester John, each more patently ridiculous than the last. And yet, there is likely some grain of truth buried within the hype (much like the legend of King Arthur or the story of Texas Chainsaw Massacre). To craft a coherent narrative from the jumbled mess of stories is virtually impossible, but then coherence is vastly overrated, so let's just plunge right in. The story of Prester John is probably best summarized in multiple choice format (you may select more than one answer in each category): (Prester John, Priesty Juan, Presbyter John) was a (king, pope, saint, caliph) in (India, Ethiopia, Asia, Africa) who had a (theocracy, monarchy, caliphate, church) of great wealth and power, possibly populated with all manner of mythical beasts, during the (10th, 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th, 15th, 16th) Century.

Unlike most legends, which generally require several centuries to propagate into massive variation and inconsistency, the tale of Prester John seemingly sprang into existence fully formed and in a half dozen variations. Early Christian legends had the original 12 Apostles spreading out to the ends of the earth in a geographically improbable dispersion to found Christian communities just about everywhere from Africa to Peru to Antarctica. Southeast Asia was one popular destination for Apostles, and the Apostle Thomas was said to have founded a Christian community in India, among other places. From this vague sort of root, the idea of Prester John grew. It's not clear what actually and truly sparked the legend, but around the middle of the 12th century, a series of letters from purportedly found their way to the court of Pope Alexander III. These letters were allegedly from the Prester himself, describing his travails and triumphs in creating a Christian kingdom somewhere off in the "East." Several documents claiming to be versions of these letters are part of the historical record, but most of them are dated to the late Middle Ages, a period of notorious historical revisionism and outright fraud. The letters contain remarkable descriptions of Prester John's kingdom. Prester John's adventures included warriors riding to battle on elephants; encounters with cannibals, pygmies and Amazons; and the locations of the Fountain of Youth and the Garden of Eden; battles with horned three-eyed humans; unicorns and phoenixes; and fabulous wealth.

The pope was pretty psyched at the notion of establishing an eastern front against the infidels, who were about to go, well, medieval on his ass. He sent emissaries to search for Prester John's kingdom, but they found only small Christian outposts, survivals of Gnosticism and other various heresies in the Near East. Further exploration turned up a bunch Taoists and samurai, which everyone agreed were very interesting but held little promise vis a vis killing Muslims, which was the order of the day. Italian explorer Marco Polo took an interest in the stories later, after the Christians had their asses kicked out of Jerusalem by Saladin. Polo never found Prester, so he made nice with Kublai Khan instead. Since the Chinese had discovered gunpowder and the Europeans had not, Polo couldn't set the precedent later adopted by other European explorers of slaughtering everyone he met and claiming the country for white guys. Instead, he kissed up to the Khan, served in a variety of governmental positions in China (the kind of thing we call "treason" these days") and wrote memoirs. The only evidence Polo ever found for Prester John were a few scattered sects of Nestorian Christians, who were more or less the first Fundamentalists, believing in the literal truth of the Bible.

The whole Prester John tale tends to incite academics into the kind of frothing rage that only other academics know or care about. There are many theories about Prester's historical origins as there are historians with Web pages and too much time on their hands. These include, but are not limited to:

|

Prester Whatever was also commonly said to have been a descendant of the Three Wise Men, who popularized gold, frankincense and myrrh by presenting these gifts to the Baby

Prester Whatever was also commonly said to have been a descendant of the Three Wise Men, who popularized gold, frankincense and myrrh by presenting these gifts to the Baby  Although none of the above (except for cannibals and elephants) actually existed, the stories themselves had a very real historical impact.

Although none of the above (except for cannibals and elephants) actually existed, the stories themselves had a very real historical impact.