|

Vince McMahon There are two Vincent Kennedy McMahons, the one who runs the a multimillion dollar public company and the one who appears as a cartoon supervillain on TV.

There are two Vincent Kennedy McMahons, the one who runs the a multimillion dollar public company and the one who appears as a cartoon supervillain on TV. No, wait, scratch that. There are one and a half Vince McMahons, because it's hard to tell where the Donald Trump part ends and the Lex Luthor part begins. VKM, the third generation of a wrestling promotion dynasty, is a man of many dubious distinctions. For instance, he is the ONLY chairman of the Board of Directors of a publicly traded company whose employees are routinely required to LITERALLY kiss his bare ass on national television. Not even Larry Flynt can make that claim (although all bets are off if he becomes governor of California)! McMahon has had more startling triumphs and humiliating defeats in his lifetime than Meatloaf, John Travolta and Bill Clinton all rolled into one. And he's only 58, which means there's time to have a lot more before he's through (not counting years deducted from his lifespan for an ambiguous volume of steroid use and whatever unmeasured-by-science statistical deviation is caused by repeatedly being struck in the head with steel chairs).

In addition to being a savvy promoter with a wide-ranging East Coast territory, the luck of the draw positioned McMahon in one of the first regions to install a cable television network infrastructure, an advantage that would prove decisive in the years to come. The senior McMahon wouldn't live to see how cable would transform his business, which is probably just as well. In 1982, he sold the promotion to his son, Vincent Kennedy McMahon. and he died two years later. VKM was the wrestling promoter to end all wrestling promoters — literally. With little direct experience in his father's business and even less cash on hand, McMahon had a vision for what wrestling could be. That vision had everything to do with television. McMahon was the first promoter to see the real potential in nationally syndicated television and the eventual emergence of national cable channels.

Vince also had a vision for where the money was coming from — pay per view, a paradigm which the WWF pretty much invented with the very first Wrestlemania in 1985. McMahon's idea was ahead of its time — the technology for PPV barely existed and few homes were wired for cable. Wrestlemania I was broadcast from Madison Square Garden via closed-circuit television to specially equipped theaters around the country.

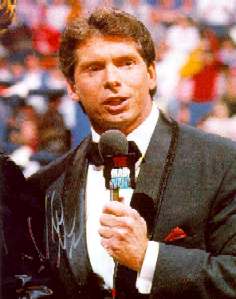

McMahon worked behind the scenes as a booker and promoter, and in front of the cameras as a smarmy pencil-necked announcer in a canary yellow suit. His new company's high visibility was driven by a young superstar named Terry Bollea, who performed under the moniker "Hulk Hogan." Hogan's steroid-fueled physique and strong interview skills more than made up for his somewhat limited repertoire of wrestling moves, and McMahon knew how to mix up the elements to play to Hogan's strengths. Other powerful WWF personalities soon became household names, such as Rowdy Roddy Piper and Andre the Giant, some of Hogan's first and most memorable adversaries. The WWF crushed the other regional wrestling promoters of the day, buying some out and simply overwhelming others. With its high-visibility superstars and McMahon's extravagant skills at promotion, WWF became synonymous with "pro wrestling." The company's business model was to make a little bit of money off cable and syndicated television shows. Aside from the relatively little revenue they generated, the shows ("Raw" on the USA network, the "Saturday Night Main Event" on NBC, "Smackdown" on UPN, and others) served the much more important purpose of selling live event tickets and pay per views. By Wrestlemania III, the promotion was in the black, and McMahon seemed unstoppable. As the soap opera storylines played out onscreen, a similar dynamic took place behind the scenes, as Vincent K. McMahon found himself locked in battle with a personality as oversized and ego-driven as his own — Ted Turner. The Atlanta mogul had long presented various forms wrestling as a staple of his innovative cable "superstation" WTBS. As McMahon stampeded over his competitors, Turner manuevered himself into position, buying a regional promotion and transforming it into World Championship Wrestling (WCW).

In 1995, Turner debuted "WCW Nitro" to directly compete with McMahon's "Monday Night Raw." A slugfest worthy of the in-ring antics ensued between the two shows, and Nitro soon managed to dominate the ratings. When Hulk Hogan signed up with Turner's promotion, McMahon considered it a personal betrayal — and he would spend the next 10 years working through those feelings in embarrassing televised displays. The WWF was down but not out. With profits in the bank and Ted Turner's bankroll at their backs, WCW management was prolific in its expenditures and careless with wrestlers' egos — which were frequently as oversized as their biceps. The battle between the two promotions broke new ground in the world of wrestling. When Vince Jr. took over the WWF, he did so with a wink and a nod to the fact that the outcomes had been predetermined, breaking a code of silence, known as kayfabe (an old carny term), which had ruled the industry for decades.

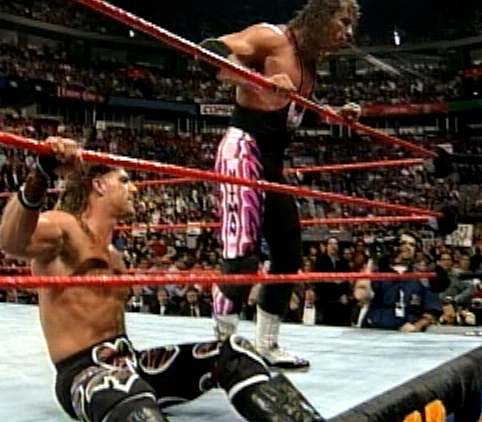

In 1997, Bret Hart was the WWF champion. He was defecting to WCW, and sacred wrestling tradition mandates that when you change promotions, you leave the title behind. The details of what happened behind the scenes in Montreal are different depending on who tells the story, but the general outline goes something like this: Hart was set to face rising young star Shawn Michaels for the championship at a pay-per-view in Montreal. Hart and McMahon negotiated about the finish of the match for a long time, and supposedly agreed that Hart would win the match at the PPV then hand over the belt to McMahon the following night on Raw. What happened instead became a wrestling legend. By all accounts, McMahon felt various levels of pique about Hart's departure, and from a business perspective, he was even more concerned about seeing the reigning WWF champion walk to the competition undefeated. The Montreal match was scheduled to include a wrestling staple known as the "ref bump," in which the referee gets "knocked out" and all manner of mayhem transpires during his nap. When the ref took his bump during the match, Michaels placed Hart in a submission hold. In addition to creating drama over whether a wrestler might submit to the pretend-painful hold, submission holds are used to allow the participants in a match to catch their breath and take a short break. Hart was expecting that he would reverse the hold long before the ref "recovered" from the bump.

Hart stalked to the edge of the ring, where McMahon was watching on the outside and spit in the boss's face. (After the show, he punched Vince out in the locker room.) In the entire history of humankind, no one ever got as much mileage out of being spit on as Vincent Kennedy McMahon. Fans were outraged, especially in Hart's native Canada (where fans to this day bring "You screwed Bret" signs to WWE shows), and the locker room was in an uproar. McMahon eventually felt enough pressure to make an unprecedented public statement about the incident in which he famously said that "Bret Hart screwed Bret Hart." The screw job had the unforeseen effect of making Vince McMahon the top "heel" in the WWF. Prior to Montreal, Vince had largely confined his onscreen appearances to the role of announcer and promoter. After Montreal, Vince was seen as a treacherous villain. He had instantly created more heat for himself than any heel wrestler in the company could hope to achieve. In subsequent interviews, McMahon would fuel the fire by blaming Hart for the fiasco, infamously stating "Vince McMahon didn't screw Bret Hart, Bret Hart screwed Bret Hart." After the nearly insane fan reaction to the events in Montreal, McMahon realized that he was potentially one of the company's biggest draws, and he booked himself into a series of battles with the WWF's rising star Stone Cold Steve Austin, which led to stellar ratings and made Austin the company's top "babyface" (good guy).

Despite his willingness to suffer (or inflict) almost any humiliation onscreen, McMahon desperately craved respectability offscreen, and in 1999, he took the WWF public at $17 a share. It was a hot property over the next few years, ranked as a top growth spot, and the company had hundreds of millions of dollars cash in the bank. McMahon became a sought-after guest in unlikely venues such as CNBC, where he presented himself much like any other millionaire corporate chairman. Except most corporate chairman don't routinely host a "Kiss My Ass Club" live on national TV. These triumphs led McMahon to believe he could expand his successes out of the world of wrestling. In 2001, McMahon and NBC joined forces to launch the XFL — Extreme Football League. On paper, it seemed like a brilliant idea, to join the theatrics and slick production values of pro wrestling with the wider audience for football. In practice, it was an unmitigated disaster, sucking tens of millions of dollars out of the company and perhaps forever ending McMahon's dream of mainstream acceptance. As WWF (rechristened WWE after another humiliating courtroom loss to the World Wildlife Fund) saw its stock plummet, McMahon refocused on wrestling and rebuilding his damaged empire in the face of a probably cyclical downturn, transforming much of his defeat and humiliation into fodder for onscreen vignettes.

Say what you will about the man, but he can take a joke. Everything from the XFL to the steroid trial to Vince's reputation for womanizing to his insane jealousy toward Ted Turner is fair game to show up as a plot element on one of his shows. Vince McMahon's staying power as a television personality isn't damaged by his personal foibles — it's magnified. Like Bill Clinton (another favorite target of McMahon's lampoons), the more he gets knocked down, the more he gets up again. There are worse qualities you could ask for in a businessman.

|

VKM's father, Vincent McMahon Sr., ran the World Wide Wrestling Federation, known as the WWWF (which later dropped the Wide), during the dawn of

VKM's father, Vincent McMahon Sr., ran the World Wide Wrestling Federation, known as the WWWF (which later dropped the Wide), during the dawn of  Wrestlemania made headlines, and it almost made money. The headlines proved to be more important, establishing the McMahon empire as the first and only wrestling promotion with a truly national reach.

Wrestlemania made headlines, and it almost made money. The headlines proved to be more important, establishing the McMahon empire as the first and only wrestling promotion with a truly national reach.  WCW surged into prominence during the mid-1990s, as Turner poured money and resources into the operation and raided McMahon's top talent (including Hulk Hogan). At the same time, the WWF was rocked by a drug scandal, when federal authorities busted a doctor who had been providing WWF superstars — and allegedly Vince McMahon himself — with illegal steroids to create the monster physiques that McMahon favored in his top stars. Hogan himself was exposed as a steroid user, a major blow to the squeaky clean superstar who had for years urged kids to "take their vitamins." In 1994, McMahon himself was charged with the distribution of illegal steroids, but he slipped out from under the charges. The stain on his reputation was more difficult to escape.

WCW surged into prominence during the mid-1990s, as Turner poured money and resources into the operation and raided McMahon's top talent (including Hulk Hogan). At the same time, the WWF was rocked by a drug scandal, when federal authorities busted a doctor who had been providing WWF superstars — and allegedly Vince McMahon himself — with illegal steroids to create the monster physiques that McMahon favored in his top stars. Hogan himself was exposed as a steroid user, a major blow to the squeaky clean superstar who had for years urged kids to "take their vitamins." In 1994, McMahon himself was charged with the distribution of illegal steroids, but he slipped out from under the charges. The stain on his reputation was more difficult to escape. As kayfabe began to disintegrate, the cosmic balance reasserted itself in a strange way. While it was increasingly acknowledged that the shows were staged and professionally written, the real-life action behind the scenes began to spill onto the camera. The most shocking example of this was an incident that arguably transformed professional wrestling forever — the infamous Montreal screw job.

As kayfabe began to disintegrate, the cosmic balance reasserted itself in a strange way. While it was increasingly acknowledged that the shows were staged and professionally written, the real-life action behind the scenes began to spill onto the camera. The most shocking example of this was an incident that arguably transformed professional wrestling forever — the infamous Montreal screw job.  But once the hold was in place, the ref suddenly jumped up, ahead of schedule, just as Hart was moving into position for the reversal. Vince McMahon, who was on the sidelines, ordered the bell to be rung. The implication was that Hart had tapped out to indicate his submission; Shawn Michaels' theme music began to play to indicate he was the victor and he was handed the championship belt.

But once the hold was in place, the ref suddenly jumped up, ahead of schedule, just as Hart was moving into position for the reversal. Vince McMahon, who was on the sidelines, ordered the bell to be rung. The implication was that Hart had tapped out to indicate his submission; Shawn Michaels' theme music began to play to indicate he was the victor and he was handed the championship belt.  Montreal was emblematic of what would follow in that it created a strange mix of onscreen and offscreen intrigues. McMahon's onscreen persona was that of an overbearing tyrant, the original "pointy-haired" boss from hell. Offscreen, McMahon was known for being almost schizophrenic in his shifts from soft-spoken and reasonable to inflexible and over-the-top.

Montreal was emblematic of what would follow in that it created a strange mix of onscreen and offscreen intrigues. McMahon's onscreen persona was that of an overbearing tyrant, the original "pointy-haired" boss from hell. Offscreen, McMahon was known for being almost schizophrenic in his shifts from soft-spoken and reasonable to inflexible and over-the-top.