|

Rotten Library > History > Inquisition

The Inquisition The English language is full of subtleties. For instance, it's good to be inquisitive. But it's bad to hold an Inquisition.

The English language is full of subtleties. For instance, it's good to be inquisitive. But it's bad to hold an Inquisition. Since the death of Jesus Christ, the one sure way to rile up the Catholic Church has been to engage in heresy. Heresy is pretty much defined as "deliberately disagreeing with the church." Historically, there have been between two billion and five billion non-Catholics living in the world at any given time since the Church was founded. That's a lot of heresy. For three hundred years or so, the early Christians were few and far between, with the result that they mostly found themselves staring at the business end of the persecution gun. This inspired a high-minded libertarian commitment to religious freedom that lasted all of 30 seconds after they took over the Roman Empire. From then on, it was "my way or the highway." Nevertheless, for the next 900 years, the battle against heresy was a loosely organized and largely non-violent affair. The wimpy Church fathers contented themselves with just writing against and occasionally excommunicating such heretics as the Gnostics. The decision to pursue this philosophical approach stemmed largely from unfavorable odds. Even after assimilating Rome, there weren't enough good, solid Christians in the power base to make the use of force an attractive option.

The first implementations of this policy were the Crusades, which involved sending armies out to forcibly convert those who didn't agree with the Pope (specifically the Muslims inhabiting the Holy Lands). The first Crusade went really well, but subsequent efforts to recapture the magic were miserable failures. After a series of embarrassing setbacks, the Church turned its attention inward, busying itself with the task of rooting out the disloyal and misguided within its own domains, primarily Europe. That's when the Inquisition was born. Technically, the Inquisition is an ongoing function of the church (more on this below), but when people talk about "the Inquisition," they're usually referring to one of two historically notable incidents: the Albigensian Inquisition, or the Spanish Inquisition. The Abigensian Inquisition was the first major operation of the sort put on by the Catholic Church. In southern France, a Christian sect known as the Cathars arose around the 12th century. The Cathars become popular in the Languedoc region of France by living a chaste and ascetic lifestyle which was considerably more in the teachings of Jesus than the local clergy, who were at the time a motley crew of fornicating, corrupt money-grubbers. The pope, motivated in large part by a lust for the wealth and lands of Languedoc, ordered a Crusade and subsequently an Inquisition in the region to stamp out the heretics and assume ownership of their property. The Crusade was very transparently about wealth and political power, so it failed to actually root out the alleged enemy, namely the Cathars. Once the mainstream Catholics had taken control of the region, they moved belatedly to squash the actual believers.

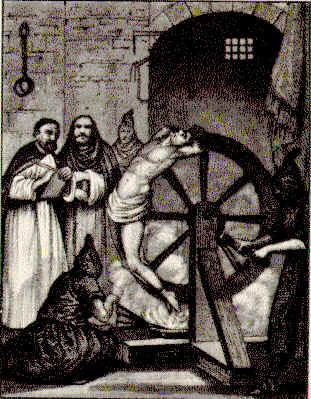

When the month expired, all hell broke loose. The monks began staging trials, with the support of the local government. Any accusation of heresy was enough to start a trial going, and the names of the accusers were kept secret. The trials themselves were held in secret. After a brief flirtation with the concept of a "right to an attorney," all due process was dispensed with. The only appeal of a guilty verdict was to the pope. The monks decided that the only way you could really be sure if someone was a heretic was to torture them extensively and creatively, just like Jesus would have wanted. Although the later Inquisitors would become far more creative in the use of machinery to support their efforts, the Dominicans were only subject to the papally decreed limit of citra membri diminutionem et mortis periculum, which meant "don't kill 'em" and "no amputations." The medieval inquisition went on for a couple of centuries, during which time a lot of scores were settled in the South of France. Everyone and anyone with a grudge could hand over their friends, families, enemies and business rivals to the Inquisitors, who were anxious to meet their quotas. The punishment for a guilty verdict in an Inquisitorial trial could range from loss of property to prison to burning at the stake. And the verdict was almost always guilty. In addition to uncounted numbers of completely innocent people, the Inquisition did succeed where the Albigensian Crusade had failed. By the time it was over, there were no more Cathars. There were also no more Knights Templar. The Knights had been a particularly wealthy and powerful secret society based in the region. The Catholics may have had other motives for killing them. Which is a whole other article. Or two or three. You probably didn't expect that we would now discuss the Spanish Inquisition. But then, nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition! In the late 15th century, a new branch of the Inquisition was formed in Spain. The Spanish Inquisition was founded on the somewhat ludicrous notion that Jews and Muslims were pretending to covert to Catholicism in order to undermine the church in Spain.

Although you might have a picture of a quaint medieval hysteria, the Spanish Inquisition went on for THREE HUNDRED YEARS, lasting well into the 1800s. The first five years of the Spanish Inquisition were basically rampant mayhem with no appreciable diminishment of the "threat" from the fake Catholics. As a result, Tomas de Torquemada was appointed to, uh, whip the Inquisition into shape. He succeeded beyond the Church's wildest nightmares. Thousands and thousands of "heretics" were burned at the stakes throughout the duration of the Spanish Inquisition (the exact numbers are unknown). There was no such thing as an "alleged" heretic under the Inquisitions reign of terror; there were only "repentant" and "unrepentant" heretics. "Repentant" heretics were those who confessed their heresy and agreed to shell over big bucks to the Church. Poor people accused of heresy (who were relatively fewer) could only save themselves with full confessions and by naming the names of other heretics. To assist people in repenting, the Inquisitors used any torture method they could think of, with the theoretical restriction that they couldn't break the skin. The Inquisitors came up with numerous gadgets to work within this restriction. They included:

Methods of execution weren't much better. Since death was the eventual outcome, the skin-breaking point was rendered largely moot. While burning at the stake was the most widely used method, being cost-effective and providing a fun spectacle for the whole family, there were other approaches used in special cases:

The last burning organized by the Inquisition was in 1834, when the Spanish Inquisition was officially abolished. But though Torquemada's legacy has been laid to rest, the Inquisition lives on. Based in Vatican City, the Holy Office of the Inquisition is still one of the most powerful branches of the Church hierarchy. In 1965, the P.R.-sensitive Pope Paul VI rebranded the Inquisition as the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, but it was still basically the Inquisition. The modern church lacked the political power to institute wide-ranging reigns of terror and torture around the world, so the Congregation has to settle for sternly admonishing its targets these days. What a comedown! Instead of being the most feared institution in the entire civilized world, the Congregation had to settle for making obscure theological pronouncements — in Latin, no less. So just in case you actually wanted to care about what they had to say, you wouldn't be able to read it anyway. In 1966, Paul VI even revoked its ability to ban books, leaving the Inquisition toothless and largely irrelevant going into the 21st century. The Congregation did have a few brief moments of shining glory in recent years, such as the pronouncement that yoga was a tool of the devil and revealing the Third Secret of Fatima, as well as endless commentaries on why Homosexuality is so darn evil. If they were smart, they'd fire up the Inquisition to deal with the whole priestly pedophilia problem. Think of the headlines! Think of the photo-ops! Especially once they dust off the Judas Chair for these guys...

|

By the 12th century, this had changed, and the Church suddenly realized the sword is actually a lot mightier than the pen.

By the 12th century, this had changed, and the Church suddenly realized the sword is actually a lot mightier than the pen.  In 1233, Pope Gregory IX pronounced the official beginning of "The Inquisition," and send a cadre of hard-ass Dominican monks to carry it out. When they arrived in town, the Inquisitors laid out a deadline: Everyone had one month to confess all your warped, evil beliefs and come back into the fold, with only a minimal punishment.

In 1233, Pope Gregory IX pronounced the official beginning of "The Inquisition," and send a cadre of hard-ass Dominican monks to carry it out. When they arrived in town, the Inquisitors laid out a deadline: Everyone had one month to confess all your warped, evil beliefs and come back into the fold, with only a minimal punishment. Since the determination of what someone secretly believes in their heart is complicated by the lack of external and incontrovertible evidence, the Spanish Inquisition quickly became notorious for a) extremely creative use of torture and b) its tendency to be unleashed on just about anyone at any time, for any reason, or for no reason at all (thus the "nobody expects" element).

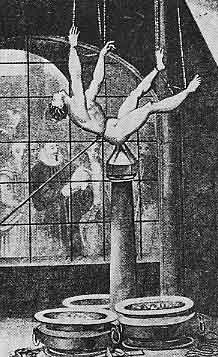

Since the determination of what someone secretly believes in their heart is complicated by the lack of external and incontrovertible evidence, the Spanish Inquisition quickly became notorious for a) extremely creative use of torture and b) its tendency to be unleashed on just about anyone at any time, for any reason, or for no reason at all (thus the "nobody expects" element).  The Judas Chair: This was a large pyramid-shaped "seat." Accused heretics were placed on top of it, with the point inserted into their anuses or genitalia, then very, very slowly lowered onto the point with ropes. The effect was to gradually stretch out the opening of choice in an extremely painful manner.

The Judas Chair: This was a large pyramid-shaped "seat." Accused heretics were placed on top of it, with the point inserted into their anuses or genitalia, then very, very slowly lowered onto the point with ropes. The effect was to gradually stretch out the opening of choice in an extremely painful manner.