|

Rotten Library > History > Great Plague

The Great Plague Long before the threat of Biological Weapons in the hands of terrorists reared its ugly head, there was simply... the Great Plague.

Long before the threat of Biological Weapons in the hands of terrorists reared its ugly head, there was simply... the Great Plague.Also known as the Black Death, bubonic plague was one of evolution's primary thinning mechanisms in the late Middle Ages. Its symptoms include high fever, chills, headache, exhaustion, a skin rash and the namesake "buboes" — hideously enlarged and swollen lymph nodes in the neck and groin areas. Without treatment, half the people infected with plague will die (with treatment, that number drops to one in 10). After bopping around the world in scattered outbreaks over the course of at least a millenium, the plague decided to settle down in Europe for a few centuries of mayhem. The plague actually arrived in Europe as the result of one of the earliest incidences of biological warfare on record, when an invading Mongol horde threw plague-infested bodies over the walls of a Genoan city-castle under seige in 1346. The strategy was a stunning success, but the collateral damage was extraordinary.

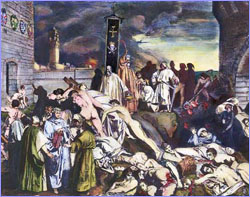

As the losing side evacuated the city, they took the plague along with them. Bubonic plague is transferred through blood; the flea-infested populace and accompanying population of flea-infested rats transferred the disease from these refugees to their new neighbors in France, Africa, Prussia, Britain, Norway, Italy and Russia. Historical accounts are pretty gruesome, such as this text from Florence in 1348: When it took hold in a house it often happened that no one remained who had not died. And it was not just that men and women died, but even sentient animals died. Dogs, cats, chickens, oxen, donkeys sheep showed the same symptoms and died of the same disease. And almost none, or very few, who showed these symptoms, were cured. The symptoms were the following: a bubo in the groin, where the thigh meets the trunk; or a small swelling under the armpit; sudden fever; spitting blood and saliva (and no one who spit blood survived it). It was such a frightful thing that when it got into a house, as was said, no one remained. Frightened people abandoned the house and fled to another.

French bishops and Spanish Kings died as easily as serfs and the working class (although the latter were more heavily impacted due to closer association with fleas). On the bright side (such as it was), this allowed workers to start demanding better wages and working conditions, since the rampant death had thinned the labor pool so severely. Although the major epidemic had largely receded by the time two decades had passed, it never quite went away, with scattered outbreaks recurring over the next few centuries. The Plague resurged for one last major European epidemic in London in 1665, an outbreak that gets a lot of attention in the history books, partly because it killed a lot of white people, but also partly because it was extraordinarily well-documented. The Great Plague of London started with a devastating outbreak in Holland a couple years earlier. In spring of 1665, it hit Britain with a vengeance. Because it started by killing off poor people, the monarchy naturally paid no attention. Then it began to climb the economic ladder, and suddenly there was a problem.

People were starting to slowly deduce the flea thing, but it was a case of trial and error. First they decided plague was being spread by dogs and cats, so the mayor of London ordered all dogs and cats executed. Despite the extermination of millions of Fluffies, Lassies, Snowballs and Spots, the plague not only persisted but actually accelerated, since the brilliant strategy of executing all the cats allowed the rats (the actual culprits) to multiply freely in the absence of their most dangerous predator. As spring stretched into summer, the doctors and government officials (now safely ensconced in country estates) decided to start forcible quarantines of plague victims. When one victim surfaced in a house, it was immediately quarantined. While this approach did help slow the spread of disease to a certain extent, it likely also resulted in thousands of additional deaths among those who were infected and their families, since the quarantine rules didn't include provisions for things like "feeding the people inside." And, of course, the armed guards outside plague houses were focused on keeping the miserable suffering people in line, and not so much on noticing if any rats were passing through.

I went all the first part of the time freely about the streets, though not so freely as to run myself into apparent danger, except when they dug the great pit in the churchyard of our parish of Aldgate. A terrible pit it was, and I could not resist my curiosity to go and see it. As near as I may judge, it was about forty feet in length, and about fifteen or sixteen feet broad, and at the time I first looked at it, about nine feet deep; but it was said they dug it near twenty feet deep afterwards in one part of it, till they could go no deeper for the water; for they had, it seems, dug several large pits before this. [...]The Great Plague of London ended when the fleas started dying as was their seasonal habit, in the fall and winter. In all, more than 70,000 people died, about 15 percent of the population of London. Inreased sanitary conditions helped reduce the threat of plague over time, and in the 19th century, scientists figured out the whole rat-flea thing. With the invention of antibiotics in the 20th century, the dangers of plague ebbed into history. An outbreak in India in 1994 resulted in tens of thousands of infections, but only 56 deaths (despite widespread panic). So the next time one of your enemies throws a plague-infested corpse into your yard, you can cheerily laugh it off and run down to the corner drug store for some tetracyclin. Just watch out for the smallpox blankets, those are killers... |

One can only hope that the Genoan city was really, really worth it. Starting in 1347 and lasting 20 years, the resulting

One can only hope that the Genoan city was really, really worth it. Starting in 1347 and lasting 20 years, the resulting  As bad as all this was, and it was pretty bad, it was just going to get worse. As the Plague spread across Europe, the death toll mounted to extraordinary levels, showing a callous disregard for class distinctions, wealth and religious authority.

As bad as all this was, and it was pretty bad, it was just going to get worse. As the Plague spread across Europe, the death toll mounted to extraordinary levels, showing a callous disregard for class distinctions, wealth and religious authority. Flight was a favored strategy for dealing with this problem, and the people who fled were, of course, exactly the people who should have stayed — the nobility (i.e., the government), law enforcement, doctors and priests all high-tailed it out of town rather than try to help the people to whom they theoretically had an obligation.

Flight was a favored strategy for dealing with this problem, and the people who fled were, of course, exactly the people who should have stayed — the nobility (i.e., the government), law enforcement, doctors and priests all high-tailed it out of town rather than try to help the people to whom they theoretically had an obligation.  Daniel Defoe, who would become famous for writing "Robinson Crusoe," penned a more or less contemporaneous semi-fictional history of the London plague, reconstructed from eyewitness accounts and his own experience with an outbreak in France a few decades later. While unfortunately penned in the virtually unreadable prose that makes Defoe a favorite of sadistic English high school teachers, it does provide some useful insight into conditions in London at the time.

Daniel Defoe, who would become famous for writing "Robinson Crusoe," penned a more or less contemporaneous semi-fictional history of the London plague, reconstructed from eyewitness accounts and his own experience with an outbreak in France a few decades later. While unfortunately penned in the virtually unreadable prose that makes Defoe a favorite of sadistic English high school teachers, it does provide some useful insight into conditions in London at the time.