|

Rotten Library > Imagery > 3-D

3-Daka 3D, stereoscopy Humanity is never satisfied. First, there were crude sketches on cave walls, then simple paints made from plants, then the more sophisticated oil paints, then photographs, then color photographs, then moving photographs, then moving color photographs...

Humanity is never satisfied. First, there were crude sketches on cave walls, then simple paints made from plants, then the more sophisticated oil paints, then photographs, then color photographs, then moving photographs, then moving color photographs... We've always been obsessed with capturing realism, but we continue to fall short of the final frontier of reproduction — lifelike three-dimensional images. It isn't for lack of trying. In terms of man-hours and creative ergs expended, the effort to produce 3-D imagery is up there with the putting a man on the moon and curing cancer. Around 300 A.D., Euclid discovered that it takes two eyes to see in three dimensions. However, the ancient Greeks were diverted by a theory that the eyes projected invisible rays that allows humans to perceive depth, a premise not unlike radar, and the "emissions" theory stood for several centuries. The search for these invisible rays distracted scientists from the fact that stereo vision is a much simpler concept. Despite this essential misconception, Euclid unraveled enough of the puzzle that an artist named Giovanni Battista della Porta was able to sketch the first stereoscopic image at the beginning of the 17th century. Sir Charles Wheatstone reinvented the wheel in 1832, by creating the first stereoscopic images. A stereoscopic image is a pair of drawings or photographs that are slightly different from each other, as if each is seen at a slightly different angle. The process mimics the slight displacement of an image as seen from the right and left eyes.

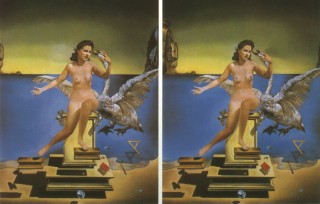

Wheatstone's initial efforts were drawings of simple cubes and cones. With the popularization of photography just a few years later, however, he adapted his technique for use in creating and viewing stereoscopic pictures, by taking a photograph of a scene from two slightly different angles and using the stereoscope to view the result. Wheatstone's apparatus was needlessly large and elaborate, and subsequent stereo viewers became smaller and less expensive, leading to a worldwide fascination with the art. Thousands of stereo pictures were produced, ranging from historic landmarks in foreign lands to personal portraits. Some of the 20th century's greatest artists learned to work with the stereoscope format, most famously Salvador Dali, who produced works that bent both mind and eye.

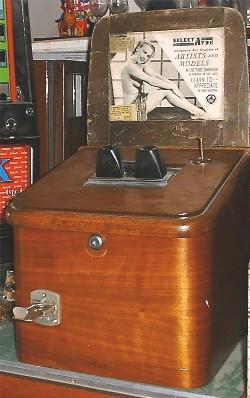

A few mechanical viewers provided the stereoscopic experience, but it was prohibitively expensive to make a machine to deliver more than a couple of seconds of footage with a poor frame rate to boot. The laws of supply and demand limited these machines mostly to peep shows and World's Fair exhibitions. Other forms of 3-D effect were extremely limited in one way or another. Mirrors and lenses could be used to create the optical illusion of a 3-D object, but the structural concerns limited this approach to the merest of novelties, since the original item had to be nearby in order for it to work. Other optical illusions create the illusion of depth with specific kinds of motion, geometric patterns or contrasting colors, but these aren't suitable for general purpose reproduction. A process called lenticular printing used a plastic filter to redirect light and create an illusion of depth in a still picture, but these were both expensive to print and limited in the amount of depth they offered. (The process, most often seen on postcards, could also be used to present extremely crude animations.)

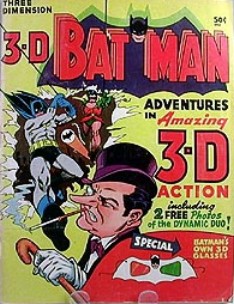

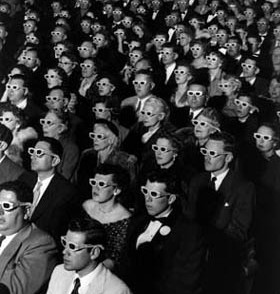

The technique was used from the earliest days of motion pictures, through the 1920s, but never particularly caught the public's imagination. In the 1950s, however, the movie industry hit a painful slump after congressional investigations of Unamerican Activities derailed Hollywood's creative momentum coming out of the 1940s. The industry heavily pushed 3-D as a new innovation to bring people back to the theaters. The first 3-D movie to hit it big was 1952's Bwana Devil, sometimes incorrectly identified as the first 3-D movie made. (It may have been the first full length feature made in 3-D, but that isn't entirely clear.) Bwana Devil was instantly the epitomy of what the entire 3-D craze would become — utter crap that was redeemed only partially by the illusion that spears, arrows and various other objects were flying off the screen into the audience. Or kinda. The '50s 3-D technology created enough depth of field to jar audience members, but not enough to create the genuine illusion that something was really flying off the screen. The red-green glasses were much more effective in comic books, however, which relied on bold simple lines rather than grayscale contours. Several popular comics were translated into 3-D versions, using the technique, a process which continues to be used occasionally today.

Some of the most successful 3-D movies were standout pornos like The Stewardess, Emmanuelle: Queen of the Galaxy and Blonde Emmanuelle. Anaglyph 3-D has also been used to create headache-inducing 3-D video games, in both arcade and home formats, with mostly forgettable results. Newer versions of the technology use glasses that dispense with the red and green lenses in favor of an electronic system that alternates the view between left and right, presumably faster than the eye can see. In addition to its sometimes uninspiring results on the big screen, the anaglyph technique had several practical limitations, not least of which was a tendency to cause headaches and eyestrain when the glasses were worn for a couple hours at a time. The commonly used red-green technique had other flaws as well, including a lack of image resolution caused by the softness of a 35mm print on the big screen and aggravated by the fact that most people have some small, unpredictable degree of color blindness.

The anaglyph 3-D method increasingly came to be used in shorter features, which minimized discomfort among viewers. These movies were frequently used at special attractions, such as theme parks and casinos, where no one was especially bothered by sitting through a 12-minute movie with no plot. As computer-generated special effects improved, 3-D was used to great effect in short features like Terminator 2: 3-D, in which CGI liquid metal monsters could be tailored to the 3-D process much more easily than Bwana Devil's leaping lions. IMAX theaters, with their massive curved screens and 70mm film, have today become the premier outlet for anaglyph 3-D movies.

The notion of true 3-D reproduction has been around for years, but it took on a peculiar cachet with the debut of Star Trek: The Next Generation, which heavily featured the "holodeck" — a mesh of technology and supporting effects to create the ultimate 3-D virtual reality environment. The "holo" in holodeck stands for hologram, the real science of using lasers to project true three-dimensional images. The word "holodeck" entered the cultural lexicon overnight, but holograms as they exist today bear virtually no resemblance to those employed on the fictional final frontier.

There are downsides to holographic printing, however, and they aren't insignificant. For one thing, holography as it currently exists can't reproduce color, casting its images strictly in rainbow hues. For another thing, holography can't be used to reproduce moving images, except for a few frames of crude motion, similar to the lenticular printing effect. There is some hope for the future, however. The fallacy of the holodeck is that light simply doesn't act the way Star Trek producers would prefer. If you force light to stand in one place and take the shape of Professor Moriarity, just for instance, it is no longer light. A holographic environment — in which you could walk around and interact with objects — is so far-fetched as to fall somewhere on the line between science fiction and science fantasy.

There are different types of "holographic" 3-D monitors; some shine lasers into a pressurized gas compartment to create its 3-D effect, others use polarizing or laser-etched light filters to combine two projected images that are seen with slight differences by each eye. Some displays literally do it with mirrors. Some project an illusion of objects extending off the screen, others are like looking out through a window. Some are tabletop displays that you can view from 360 degrees. It's a start, but there isn't an industry standard yet, and display technology tends to lag far, far behind the computers to which they link. These devices are too expensive for most consumers who are not the Defense Department. Expect to spend upward of $10,000 just for the monitor, let alone the extremely high-end computers needed to produce even a simple 3-D video. You would have to be a highly motivated Trekkie indeed to mortgage your house for a holodeck that doesn't include interactive prostitutes made of hard light. If you can't wait 20 years to have your holographic horizon broadened? Well, we hear Bwana Devil pops up on AMC every now and then...

|

Wheatstone designed a stereoscope that would remain largely unchanged for decades, a binocular-style viewer that forces the eyes to combine the two images into a single, "stereo" image that creates an illusion of depth. A simple stereo viewer can easily be made out of construction paper, or you can create the effect with more difficulty by reverse-crossing your eyes — i.e., letting your field of vision stretch past the image as if you were looking at something behind the images so that the twin pictures become a single, stereo image.

Wheatstone designed a stereoscope that would remain largely unchanged for decades, a binocular-style viewer that forces the eyes to combine the two images into a single, "stereo" image that creates an illusion of depth. A simple stereo viewer can easily be made out of construction paper, or you can create the effect with more difficulty by reverse-crossing your eyes — i.e., letting your field of vision stretch past the image as if you were looking at something behind the images so that the twin pictures become a single, stereo image.  Stereoscopy arguable reached its technological peak in 1939, the debut of the Viewmaster, a cheap, handheld stereo slide viewer that offered seven images at a time, viewed in sequence using a lever on the side of the device.

Stereoscopy arguable reached its technological peak in 1939, the debut of the Viewmaster, a cheap, handheld stereo slide viewer that offered seven images at a time, viewed in sequence using a lever on the side of the device.  Later models offered innovations such as soundtracks, electric backlighting and motorized slide switching, but the basic stereoscopic technology had plateaued. The major limitation was the solitary nature of the novelty. Stereoscopy was a serial pleasure at best; only one person could view an image at a time. But the fastest-growing medium of the day provided a community experience — motion pictures.

Later models offered innovations such as soundtracks, electric backlighting and motorized slide switching, but the basic stereoscopic technology had plateaued. The major limitation was the solitary nature of the novelty. Stereoscopy was a serial pleasure at best; only one person could view an image at a time. But the fastest-growing medium of the day provided a community experience — motion pictures.  The real breakthrough in 3-D imagery had already been invented, it just hadn't caught on it. The inventor of 3-D glasses was a man named Joseph D'Almeida, who in the 1850s developed the concept of "anaglyph" stereo, in which dual images tinted red and green were projected on a screen. Viewers wore glasses that had one red lens and one green lens, which filtered the image to present a passable illusion of depth. An improved version of the anaglyph process used polarized lenses that eliminated the red-green tinting.

The real breakthrough in 3-D imagery had already been invented, it just hadn't caught on it. The inventor of 3-D glasses was a man named Joseph D'Almeida, who in the 1850s developed the concept of "anaglyph" stereo, in which dual images tinted red and green were projected on a screen. Viewers wore glasses that had one red lens and one green lens, which filtered the image to present a passable illusion of depth. An improved version of the anaglyph process used polarized lenses that eliminated the red-green tinting.  Creatively, 3-D producers had a tendency to skimp on such nonessentials as "good writing" and "fine cinematography." Nevertheless, a few semi-classics did come out of the 3-D era, such as It Came From Outer Space, The Creature from the Black Lagoon and House of Wax. Artistically, one of the better examples of the genre was The Mask, which featured surreal 3-D horror sequences interspersed with regular footage.

Creatively, 3-D producers had a tendency to skimp on such nonessentials as "good writing" and "fine cinematography." Nevertheless, a few semi-classics did come out of the 3-D era, such as It Came From Outer Space, The Creature from the Black Lagoon and House of Wax. Artistically, one of the better examples of the genre was The Mask, which featured surreal 3-D horror sequences interspersed with regular footage.  Because of these drawbacks, the anaglyph method had a limited appeal. Even by the end of the '50s, audiences had largely burned out on the concept. 3-D movies continued to be made, but they became a rarity, eventually being reserved for special attractions such as the third movie in a franchise series that was otherwise running on fumes — such as Jaws 3D, Amityville 3D

and Friday the 13th Part 3.

Because of these drawbacks, the anaglyph method had a limited appeal. Even by the end of the '50s, audiences had largely burned out on the concept. 3-D movies continued to be made, but they became a rarity, eventually being reserved for special attractions such as the third movie in a franchise series that was otherwise running on fumes — such as Jaws 3D, Amityville 3D

and Friday the 13th Part 3.  Even with the significant improvement in 3-D technology that IMAX represents, there is a practical limitation on all of the abovementioned technologies. They're not true 3-D, only simulation via stereoscopy. You can't get up out of your seat and walk around an object, viewing it from every angle.

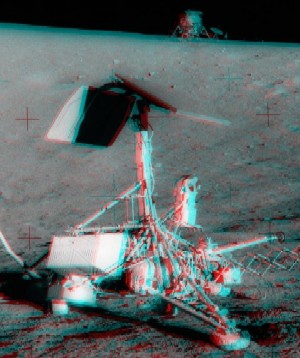

Even with the significant improvement in 3-D technology that IMAX represents, there is a practical limitation on all of the abovementioned technologies. They're not true 3-D, only simulation via stereoscopy. You can't get up out of your seat and walk around an object, viewing it from every angle.  Modern holograms are three-dimensional images reproduced on a photographic medium. Holograms use microscopic etchings angled to trick the eye into perceiving depth where there is none. While the result of a hologram is still not "real" 3-D, the technology potentially offers a great improvement over stereoscopy, since viewers are not required to wear a special apparatus and you actually can walk around an image to view it from different angles.

Modern holograms are three-dimensional images reproduced on a photographic medium. Holograms use microscopic etchings angled to trick the eye into perceiving depth where there is none. While the result of a hologram is still not "real" 3-D, the technology potentially offers a great improvement over stereoscopy, since viewers are not required to wear a special apparatus and you actually can walk around an image to view it from different angles.  That doesn't mean that lasers can't be used to produce 3-D effects today, however. A new generation of autostereoscopic displays — 3-D without glasses — is now being born. Most of these displays are not correctly referred to as holographic, but try telling that to the marketing department.

That doesn't mean that lasers can't be used to produce 3-D effects today, however. A new generation of autostereoscopic displays — 3-D without glasses — is now being born. Most of these displays are not correctly referred to as holographic, but try telling that to the marketing department.