|

Rotten Library > The Occult > I-Ching

i-Ching People have a tendency to lump the i-Ching in with fortune-telling systems such as the Tarot, Palmistry or Astrology. And, to be fair, there are some passing similarities, in the same way that a Fisher-Price toy airplane has a passing similarity to a stealth bomber — it's not just a matter of scale, it's also the question of whether it flies.

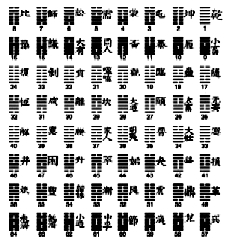

People have a tendency to lump the i-Ching in with fortune-telling systems such as the Tarot, Palmistry or Astrology. And, to be fair, there are some passing similarities, in the same way that a Fisher-Price toy airplane has a passing similarity to a stealth bomber — it's not just a matter of scale, it's also the question of whether it flies. i-Ching is an ancient Chinese text whose name translates as "The Book of Changes." Although it's commonly used for divination or fortune-telling, that's not its primary purpose. Some people argue that it's strictly a philosophical text, but they're also missing the point. It's difficult to pin the i-Ching down to just one word, topic or field. But it's got more in common with physics than fortune cookies. i-Ching is about 4,000 years old, give or take 1,000. Legend states it was written by a man named Lao Tsu, which is good enough for a Jeopardy answer, but probably not literally correct. Then again, who knows. After about 3,000 years of history, things start to get fuzzy. The Book of Changes is based around a geometric construction called a hexagram, which consists of six horizontal lines stacked vertically. Each line is either a solid line, representing yang or a broken line, representing yin. The first religion to outline the qualities of yin and yang was Taoism, although the principles have subsequently been adopted by Buddhism, some branches of Hinduism and tattoo lovers everywhere. Yin is primarily characterized as flexibility, while yang is taken to be firmness. Over the course of centuries, these qualities have expanded to encompass a fairly lengthy set of descriptive metaphors, including:

All these may be useful for examining various elements of philosophy and components of the i-Ching itself, but they're mostly just revisionist tinkering with the original concepts. The main points to remember here are firmness and flexibility. If you take the six lines of the hexagram, and factor in the yin and yang qualities of each line, you get a total of 64 possible combinations, each made up of a pair of trigrams with one of eight symbolic elemental associations — fire, lake, earth, thunder, water, wind, sky and mountain (the exact symbol used will vary wildly depending on who you talk to). The actual Book of Changes itself is a dictionary of the meaning of each of the hexagrams. While it varies from translation to translation, the passages typically go something like this:

35. AdvanceAnd so on. Now, you're probably thinking that this doesn't sound very accessible, and why should it? Based on the best estimate of the Rotten.com user profile, you're probably not a Taoist (which would be very helpful to you in grokking the above). Plus the book was written 3,000 years ago. In light of this, there are people who believe that the best way to handle the i-Ching is to boil it down to something that you might get for a penny from a machine that also tells your weight. Something like this:

28. Ta Kuo (Preponderance of the Great)While this all seems pretty basic and not dissimilar from a divination system like the Tarot, in which each card has a proscribed meaning, there's actually a lot more to the i-Ching than immediately meets the eye. For starters, the hexagram system of the i-Ching is actually the first recorded binary system of counting in history. Since we're working with yins and yangs here, it's pretty easy to see how that translates into ones and zeros. The binary interpretation of the i-Ching opens up a can of worms — or fifty. For one thing, the system immediately falls into correspondence with the elaborate system of circuits and chips you are using to read this page, which is structured around multiples of 8, 16, 32, 48 and 64. For another thing, there just happen to be 64 "codons," or nodes of information, in the DNA which makes up your personal wetware.

When people first started noting these qualities of the system in the '70s or thereabouts (the binary part was noticed earlier), there was a groundswell of excitement among the outer fringes of the scientific community, and many people rushed to start cataloging the ways that the i-Ching corresponded to the physical world. While no one's picked up a Nobel prize for such an investigation yet, there's still a lot of people working on it, to varying degrees of scientific and/or pop literature success. The reason the i-Ching works so well in analyzing physical systems is that, at its heart, the book really sets out to provide a model of system processes. By counterbalancing firmness and flexibility in varying quantities and with line positions that each represent a state of time and/or space, the hexagrams were actually originally meant to model the process of how change takes place.

The i-Ching trigrams each represent a broad process or quality; the hexagrams represent the mix and interplay of the eight basic processes. Interpretations of the hexagrams like those above are, when read very literally, a detailed analysis of how these binary quantities (lines) move into the processes (trigrams) and then into a system (hexagrams). So in any given situation, you can pick it apart in detail, break it down for the meanings of each line and trigram, and assign yin and yang to each line based on your evaluation of the facts. The resulting hexagram is intended to provide insight into the process of which you are a part. Now, to actually perform that kind of analysis is incredibly time-consuming and requires a sound mind, a centered psyche and a certain amount of realism in addressing your place in the world. Naturally, virtually no one wants to be bothered with going to all that trouble. That's where the fortune-telling comes into it. In lieu of a long, strenuous quest for thoughtful self-knowledge, the general practice is to randomly select a hexagram and just kind of assume it's meant to reflect your life, perhaps thanks to the vagaries of chaos theory (the i-Ching is frequently lumped in with chaos theory, in books like "The Tao of Chaos" and deranged head trips like those of Terence McKenna).

The next most common method is using coins. You toss three coins, with heads representing yang and tails representing yin (or vice versa if you feel like it). Majority rules. For those interested in authenticity, you can go down to any New Age shop and pick up some genuine "i-Ching coins," but pennies will do. Advanced users can also employ this method to figure out "transforming lines." When you have two heads and one tails, it's considered yang transforming into yin and yields a few additional lines of text. The absolute most authentic traditional approach, for the purists out there, is to pull yarrow stalks out of a bag. Yarrow is a Chinese plant with stalks. The yarrow sticks are marked for yin and yang, and you arrange them into a hexagram. Presto! You have a reading. The absolute least authentic approach, but one which is from a pure theory standpoint no worse than any other, is using a Web site to select your i-Ching text. In addition to being the second easiest approach, it saves you the trouble of flipping through one of those oh-so-retro "books" your grandfather is always going on about (if you don't mind settling for the worst of all possible translations). Technically, the i-Ching is not set up to tell you anything about your future, as even a casual reading of the text will quickly establish. It's more of a cosmic conscience, advising you on the correct way to live your life, based on your current circumstance. Depending on the translation, this advice comes in Taoist and Buddhist flavors, as well as in a blandified sugar-laden New Age variety. The fact that it's not supposed to be used to tell the future doesn't mean squat of course. I mean, when was the last time the i-Ching police kicked in someone's door and demanded they stop with the fortune telling? And lots of people do it. In fact, they've been doing it almost since the book was written, so (as the i-Ching itself would say) there is no blame. It's more intellectually sound than a palm-reading, and it's only a wee little bit crass, so knock yourself out. But do us all a favor and don't go get that yin-yang tattoo until you've bothered to learn what it means, OK?

|

Advancing, a securely established lord presents many horses and grants audience three times a day.

Advancing, a securely established lord presents many horses and grants audience three times a day.

The present is embodied in Hexagram 28. We see a beam that is weak. Under these conditions, there will be advantage in moving in any direction at all. There will be success. There are no changing lines, and hence the situation is expected to remain the same in the immediate future. The things most apparent, those above and in front, are embodied by the upper trigram Tui (Lake), which represents joy, pleasure, and attraction. The things least apparent, those below and behind, are embodied by the lower trigram Sun (Wind), which represents penetration and following.

The present is embodied in Hexagram 28. We see a beam that is weak. Under these conditions, there will be advantage in moving in any direction at all. There will be success. There are no changing lines, and hence the situation is expected to remain the same in the immediate future. The things most apparent, those above and in front, are embodied by the upper trigram Tui (Lake), which represents joy, pleasure, and attraction. The things least apparent, those below and behind, are embodied by the lower trigram Sun (Wind), which represents penetration and following. The mathematical qualities of the i-Ching are extraordinarily complex and subtle, so they lend themselves to creative arrangements. A LOT of books have been written on this subject, dating back to about 800 B.C. and continuing right up through last week. The arrangements all seem to have a certain elegance about them, and usually they can be tied to the actual meanings of the hexagrams, which encourages yet more experimentation with the layout.

The mathematical qualities of the i-Ching are extraordinarily complex and subtle, so they lend themselves to creative arrangements. A LOT of books have been written on this subject, dating back to about 800 B.C. and continuing right up through last week. The arrangements all seem to have a certain elegance about them, and usually they can be tied to the actual meanings of the hexagrams, which encourages yet more experimentation with the layout.  When you boil physical properties down to their most basic sorts of quantities, at the atomic, genetic or even the

When you boil physical properties down to their most basic sorts of quantities, at the atomic, genetic or even the  There are several methods by which one can apparently invite chaos theory into one's parlor. The easiest is that you go buy a copy of the i-Ching and randomly open it to a page. Then you read what's on the page and apply it to your life and/or your expectations for the immediate future.

There are several methods by which one can apparently invite chaos theory into one's parlor. The easiest is that you go buy a copy of the i-Ching and randomly open it to a page. Then you read what's on the page and apply it to your life and/or your expectations for the immediate future.